St George – the Patron Saint of England

It’s almost April 23rd. Which means it will be St George’s day. You know, the patron saint of England. The red cross on the white ground that is the English flag that in turn is part of the Union Jack? Yep, that’s the cross of St George.

Now you can spot the flag of St. George in the bunch!

Of late though – by that I mean since the 18th century – poor George has been receiving less attention, less celebration than his Welsh (St David), Scottish (St Andrew) and Irish (St Patrick really takes the biscuit when it comes to merriment on a feast day) saintly counterparts. Which is a shame as George has been a part of English cultural identity for the better part of 1400 years.

Not bad going for a chap martyred in Palestine somewhere near a small town called Lydda during the reign of the Roman Emperor Diocletian (284-305 AD). That’s pretty much all we know about the man. Since the 4th century the mythical layers that have built up around the saint range from the humdrum to the downright fantastical. George was supposedly an officer in the Roman army who converted to Christianity. He was killed for his beliefs not once, not twice, but THREE times, chopped into bits first time round, buried alive the next and burned in a fire the final time. Fortunately divine intervention …. ermmm … intervened and George arose unscathed. In addition he was credited with resurrecting people from the dead himself, causing wooden beams to shoot forth leaves, destroying idols and armies as well as the all important conversion of Pagans.

We can trace these particular legends back to the 6th century. A jolly long time ago. What’s rather interesting is that the first reference to St George in England is from the 8th century thanks to the Venerable Bede whilst there was certainly a church dedicated to George by the 9th. That’s quite a speedy uptake considering we’re in an age well before the internet. Or telephones. Or a reliable postal service.

No wonder the Middle Ages are sometimes called the Dark Ages. How did people survive without a reliable post service?!

The English fascination with George became more intense during the High Middle Ages. You see, England as a country was starting to get a bit more belligerent, a bit keener on trying to conquer other people (like the Welsh, Scots and Irish … oh, as well as the French) and joining pan-European military ventures like the Crusades. A martial saint like George seemed as good a patron for such martial endeavors as any. English ships and armies sported the penant of St George with pride whilst his name was invoked as a battle cry during some of the bloodiest altercations of the period. Shakespeare’s “Cry God for Harry, England, and Saint George” just before the Battle of Harfleur in Act III of Henry V is a spine-tingling taste of how powerful and real the saint’s presence was to the Medieval and Early Modern Englishman.

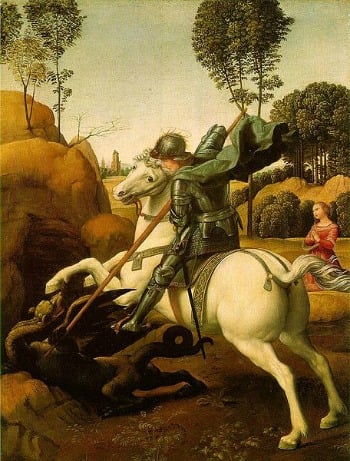

I’m sure this is precisely the image all those medieval Englishmen had of St George before going into battle.

“That’s marvelously interesting”, I hear you mutter, dearest London Perfect readers, “but what about the DRAGON?!” It’s possibly not a surprise to learn that this event was a myth. Its origins are possibly from images in the Eastern Church that depict St George spearing a dragon, a common symbol for Satan, with a female figure in the background. She is supposedly the Emperor Diocletian’s wife, who was so impressed by George that she herself converted to Christianity … and then suffered a similar fate to George for her efforts. These images were probably brought back to Western Europe during the Crusades, becoming a visual source for the first written version of St George and the Dragon in the top literary bestseller of the Middle Ages, Jacopo de Voragine’s Golden Legend of c.1260.

A Byzantine icon of St George from the Medieval period. Can you spot the princess?

Hence lots of Georges and dragons littering art and literature since then.

Oddly, although St. George’s day was a properly recognized feast day in England and continued to be so after the Reformation and the discarding of terribly popish practices like saint’s days, there were never set rituals or rules for how to celebrate. Even by the late Medieval period, how people observed April 23rd was particular to each community. Although venerated by all England, each Englishman had his own way of venerating the enigmatic St George.

Which is probably why today’s Englishman might morris dance, or consume his own body weight in beef or pretend to fight dragons to celebrate St George’s day. Want to celebrate St George’s day with a Morris Dance? Here’s a taster of how to Morris Dance.

But only with a select group of chums. In a slightly disorganized manner. Not an en masse manifestation of patriotic pride in our patron saint, like the Welsh, Scots or Irish. Which is a pity as it seems we used to be rather good at doing just that en masse, particularly moments before battle. But, in the meantime, dragon taming, Morris dancing and a hog roast in Trafalgar Square seem like a good way to go …

_____________

Zoë F. Willis is a writer and enthusiastic London resident. You can read more about her adventures and creative exploits at https://thingswotihavemade.blogspot.co.uk/

Image Credits: Saint George and the Dragon by Raphael, British Flags by Matt Buck, UK Post Box by Andrew Dunn, Lego St George’s Day by Jonathan Beard, St. George Byzantine Icon

[…] and the start of the Hanoverian dynasty (1714-1837). Oddly it took a German to assume the name of England’s patron saint. But considering George I was […]